Category: Finance, Business, Management, Economics and Accounting

ORIGINAL

Millennial consumer’s stance toward sustainable fashion apparel

La postura del consumidor millennial ante la moda sostenible

Beeraka Chalapathi1,2

![]() *, G. Rajini2

*, G. Rajini2

![]() *

*

1National Institute of Fashion Technology, Tharamani, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India.

2School of Management Studies, Vels Institute of Science Technology Advanced Studies (VISTAS). Pallavaram, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India.

Cite as: Chalapathi B, Rajini G. Millennial consumer’s stance toward sustainable fashion apparel. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología - Serie de Conferencias. 2024; 3:885. https://doi.org/10.56294/sctconf2024885

Submitted: 03-02-2024 Revised: 20-04-2024 Accepted: 10-06-2024 Published: 11-06-2024

Editor: Dr.

William Castillo-González ![]()

ABSTRACT

Sustainable fashion is the emerging fashion trend in Global fashion. In India, 34 % of population is a potential millennial contributing to the Indian economy. The present study examines the relationship of quality consciousness, price consciousness, availability of apparel, benefits, and Environmental concern on post-purchase behaviour of sustainable apparel and millennial consumer satisfaction. The results of a quantitative study using the Hayes process, it reveals that brands need to create more awareness of sustainable apparel among the millennial consumer. Price and perceived benefits are major influencing factors among millennial consumers.

Keywords: Sustainable Fashion; Millennial Consumers; Price Consciousness; Perceived Benefits; Consumer Satisfaction; Post Purchase Behaviour.

RESUMEN

La moda sostenible es la tendencia emergente en la moda mundial. En la India, el 34 % de la población es un millennial potencial que contribuye a la economía del país. El presente estudio examina la relación entre la conciencia de calidad, la conciencia de precio, la disponibilidad de la ropa, los beneficios y la preocupación medioambiental en el comportamiento posterior a la compra de ropa sostenible y la satisfacción del consumidor millennial. Los resultados de un estudio cuantitativo que utiliza el proceso Hayes revelan que las marcas necesitan crear más conciencia sobre la ropa sostenible entre el consumidor millennial. El precio y los beneficios percibidos son los principales factores de influencia entre los consumidores millennials.

Palabras clave: Moda Sostenible; Consumidores Millennials; Conciencia de Precio; Beneficios Percibidos; Satisfacción del Consumidor; Comportamiento Post-Compra.

INTRODUCTION

Fashion has been increasingly important in the twenty first century in almost every culture. Individuals, say,(1) have wasted their lives worrying too much about what other people think of their sense of style. The term sustainable fashion refers to an approach to the design, production, distribution, and consumption of clothes that minimizes its impact on the natural environment at each stage of the process. Ecologically and socially sound production and distribution of clothing and other items is at the heart of the concept known as “sustainable fashion.” The term “accessible” appears in this definition of sustainable fashion to indicate that the phrase shouldn’t be restricted to creating or purchasing brand-new items. Sustainability advertising has tricked us into thinking that by purchasing certain products we may help the environment, but unfortunately this is not the case. According to(2) Sustainable clothing is essential if we’re trying to avoid problems like green washing that have plagued businesses with a more established commitment to sustainability. Over the past few decades, as awareness of environmental concerns has spread over the world, so too has the movement toward sustainable clothing. There has been a rise in the desire for environmentally and socially responsible solutions in the fashion industry, prompting many companies to incorporate sustainable practices into their merchandise and even their corporate strategy. As a result, the fashion industry has no choice but to become more eco and socially-aware.(3,4) The garment trade is a convoluted industry that has drained societies and ecosystems around the globe. Sustainable fashion initiatives integrate sustainability, financial, and social strategies to reduce their negative impact on the environment and the lives of workers while increasing their bottom line. To the dismay of designers, marketers, and labels everywhere, the notion of environmentally friendly fashion has emerged as a major concern for the fashion industry at large.(32) Key sustainability goals, global evaluations, and global fashion tools for environmental information motivate and inform garment businesses to make big changes. Along with(4) It’s no secret that the fashion business is a major polluter, but nobody seems to notice the damage they’re doing to our planet. Most people don’t immediately associate the things they put on their bodies every day with pollution, but rather with the burning of coal and fossil fuels. Thus, eco-movements have not specifically attacked the fashion business.(33,34) The Indian apparel sector has seen significant transformations as a result of numerous factors, including shifting demographics and the increased accessibility of international fashion brands. Green and organic clothing companies are gaining popularity in India, and this trend is likely to have an impact on the income generated by the apparel industry. Organic apparels have been created by international and national clothing companies as a means of catering to customers that are environmentally sensitive.(9) Sustainability can’t be a passing trend; it must become ingrained in one’s way of life. It’s about picking your outfit, meal, and vacation destinations with care. It is crucial that we not just to respond to fashion and patterns but also come up with solutions so that customers may be conscientious about their purchases while still looking their fashionable best. The environmental costs of the fashion industry’s growth are high.(31) A worldwide effort is currently underway to encourage people to engage in more responsible social and ecological behaviours as a result of rising concerns about the effects of pollution and consumerism on the natural world. In addition, it necessitates a radical change in consumer behaviour, with more people opting to buy environmentally friendly goods. In order to increase the sales for and dedication to sustainable garment consumption, it is crucial to get an understanding of the elements that drive consumer buying decisions.(14)

The outfits sold by Fabindia have a contemporary aesthetic, but they are created using time-honoured methods such as handloom weaving and the addition of handcrafted decorations. According to(10) each ensemble that emerges from Fabindia demonstrates a kind-hearted regard for the natural world. Fabindia not only offers a diverse selection of stylish goods, but it also facilitates the connection of rural artisans with urban customers. This not only provides rural artists with the opportunity to find work, but it also helps to preserve the handmade products of India. In addition, the brand’s apparel lines now feature the age-old Gudri method. This method of making use of discarded, residual, and wasted fabric pieces from dressmakers and textile factories helps to cut down on recyclable materials. The company claims that Rajasthan and Gujarat states are its primary textile sourcing locations.

Nicobar is an Indian fashion label that prioritises modernity, mindfulness, and style. Since the beginning of the company, their primary goal has been to develop a contemporary Indian way of life, both in terms of how they wear and how they view the outside world. This is the driving force behind all that Nicobar undertakes. Their apparel and housewares are characterised by a modern take on the traditional Indian design aesthetic. They hope that by doing this, they can bring more joy into people’s lives. As per(11) Nicobar is driven by the principles of designed to meet the needs and continuous improvement, and their goal is to make products that are aesthetically pleasing and useful for consumers who desire to feel a relationship to the brands that they purchase. Inspired by the beauty of the outdoors, Nicobar is an Indian eco-friendly clothing label. In spite of its many benefits, sustainable clothing has a reputation for being prohibitively expensive. That’s why the team at Nicobar showed up with their motto: make stuff that lasts. They encourage their clients to buy less on impulse and more intentionally so that they can create a conscious wardrobe.

As an offshoot of the pioneering Bombay Hemp Company, B Label is working to improve public perception of hemp in India. The little company’s goal, expressed through a sparse line of garments, is to inform consumers about the fiber’s positive impact on the environment.(13) B Label is a popular new Indian label that has promoted and advocated for the use of organic materials in garments. Increasing numbers of people in India are starting to see the environmental damage that fast fashion does and are making the switch. Quality has not been sacrificed in the production of eco-friendly apparel. They have a modern look, are built to last, and won’t break the bank.

Ka-Sha promotes sustainability in general, but up cycling and trash control is crucial to its operation. It not only encourages other designers and fashion firms to employ recycled or repurposed materials, but also does so itself. As part of its commitment to social responsibility, the company has established Heart to Haat, a programme that repurposes unwanted items into new apparel and home goods in order to raise environmental consciousness and educate the public about the need of reusing and recycling. No fabric or substance should be thrown away if it may be put to another use. They often make use of scraps of fabric that remain after we’ve finished cutting out our items, and we often find creative ways to reuse Ka-Sha products and fabrics that have minor flaws.

According to,(8) Generation Y, often known as millennial, is regarded as the largest consumer group as well as the dominating sector of consumers, as they have a lengthy future of possible purchase intention and an annual estimated purchasing power of $200 billion. Millennial are defined as those who were born during 1981 and 1996; as of 2018, their ages range from 22 to 37 years old. Millennial customers represent the most attractive category when it regards fashion products, especially garments, and have shown a readiness to transition towards further sustainable procedures, as according,(3) The voices of Millennial have historically been the first to demand alteration. They have a lot of responsibility and dependence on others when it pertains to environmental sustainability. Those people are the only ones who can see how the present day’s actions are affecting the environment, and thus their future. They realize that if they don’t take sustainable measures now; coming generations would be forced to make do with a world devoid of much of its stunning features. We should all do our best to do what we preach and instill in the next generation the values of vegetarianism, sustainability, and tree planting. We wish to add our voice to the chorus of voices calling for a shift in emphasis toward more eco-friendly methods of clothing production. Postmodernism, armed with the knowledge at its fingertips courtesy of the Internet, has made sustainable consumption a worldwide priority.(5) According to research(6), members of Generation Y (also known as Millennial) are well-informed about ecological, societal, and economic issues. Yet, studies show that millennia’s environmental attitudes may not translate to current behavior.(7) That is to say, today’s youth actually do show that they care about the environment. Generation Y knows exactly what it is that companies stand for. When making purchases, we give our money to businesses that share our beliefs. Companies that uses recycled materials or eco-friendly dye, guarantee fair labor practices down the entire value chain, and seek out to customers to show they care about the planet and its residents may have a bright future in the fashion industry. On the other hand, it could be a site with excessive garbage, polluted water, and poorly treated employees. According to research conducted(12) the millennial generation has to use their purchasing power to push for more environmentally friendly practices in the manufacturing sector. More can (and should) be done by businesses to promote sustainable, cruelty-free fashion. Despite the fact that it’s only a gimmick to attract customers, Millennial will find it to be quite appealing. Sustainable techniques are gaining traction in the fashion business. This movement for alteration is being propelled by the specialists inside the sector taking on greater and greater levels of responsibility. The focus of this investigation is on finding sustainable fashion approaches. There will also be the development of a prototype mobile app highlighting eco-friendly brands. The Millennial consumer base will be influenced to buy more eco-friendly garments. Efforts are under way to reduce the demand for such clothing. Recent years have seen a rise in the visibility of these discussions as the world has been gripped by a pandemic for the better part of two years. Buyers from Generation Z and millennials in especially are conscious of the environmental impacts of the fashion industry and are demanding solutions. Younger populations, which make up the bulk of fast fashion consumers, are increasingly agitating for change. Millennials are now becoming increasingly conscious of the long-term effects of fast fashion’s low prices. People are becoming more knowledgeable about the origins of their clothes and the processes that go into making them. Most millennials, upon coming to this understanding, will wish to take action to protect the Earth they now call home. They’re a friendly and helpful group. They can’t stand by and do nothing as horrible incidents occur to our environment, so supporting ethical fashion brands is only one little part of their heroic effort to preserve the globe.

Theoretical framework

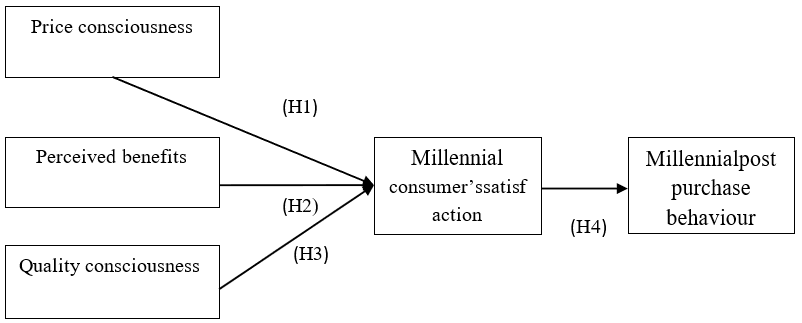

Figure 1. Hayes models of millennial consumers towards sustainable fashion apparel

Price Consciousness (PC)

Simply said, pricing is the sum of money a seller asks for a good or service. In a broader sense, pricing represents everything that consumers are willing to give up in exchange for the advantages of acquiring and using a good or service. Overall, cost has been the most influential factor in determining consumer behavior. In addition, pricing continues to be a major factor in a company’s capacity to capture and retain customers and generate revenue. The only variable in the marketing strategy that contributes to revenue generation is price. One of the adaptable parts of the marketing mix is price. There is a favorable correlation between price awareness and intent to buy. A consumer’s propensity to make a buy is best predicted by the amount of money off the original price, followed by familiarity with the brand and the business itself. And as(25) showed, price cuts increase shoppers’ propensity to make a buy. Shown in figure 1 Hayes models of millennial consumers towards sustainable fashion apparel.

H1 Price consciousness has significance effect on millennial consumer’s satisfaction.

Perceived Benefits (PB)

Perceived benefits are what motivate a given conduct. Consequently, these motives are rewards that affect the propensity to engage in a specific behavior.(24) To bridge the second and third findings gap, it is necessary to clarify the impact of perceived benefits for commercial fashion rentals. Sharing is considered both economically and ecologically advantageous type of purchasing.(23) The self-determination concept classifies these advantages as both intrinsic and external motives. It is believed that intrinsic motivation produces intrinsic fulfillment and internal satisfaction, whereas extrinsic drive pursues external goals including such prizes and recognition. Perceived monetary benefit, characterized as economic advantage, is categorized as extrinsic incentive according to previous research, but perceived sustainability impact is characterized as sustainable advantage.

H2: Perceived benefits have significance effect on millennial consumer’s satisfaction

Quality Consciousness (QC)

Millennials have expressed a need for more convenient access to eco-friendly clothing options. Purchase intention can be formed if people are familiar with the brand through direct or indirect exposure.(27) Therefore, as consumers become familiar with the brand, they may begin to form impressions based on those impressions.(26) A consumer’s propensity to make a purchase can be measured along several aspects, and that one of them is their level of brand awareness. However, the principles underlying the two variables are distinct, resulting in distinct patterns of customer behaviour. Without customers’ previous knowledge and experience with a brand, it is impossible for them to form connections with that brand.(28) An approach that has received a lot of attention for lowering the negative effects that the clothing business has on the environment is increasing the amount of time that garments can be worn by improving their quality. Despite the fact that quality is an essential component of clothes, defining quality can be difficult. Furthermore, customers have diverse methods of perceiving quality in products they purchase. Consequently, it is necessary to broaden people’s perceptions of the quality of apparel.(29)

H3: Quality consciousness has significance effect on millennial consumer’s satisfaction

Consumer’s Satisfaction (CS)

Research into fashion products has led to a significant underestimation of the importance of the after-sale phase in services. Repeat business and word-of-mouth advertising are both impacted by customer satisfaction, according to a study conducted by Harrison and colleagues. Word-of-mouth advertising has helped highlight the significance of happy customer’s information. It’s safe to say that a service company relies heavily on their customers’ happiness to stay in business consumers of it. Despite the fact that brand equity is still a major component in the pleased.(30) Consumers are thought to have an impact on a company’s long- term health through their purchasing habits.

H4: Millennial consumer’s satisfaction has positive influence on millennial post purchase behaviour and customer’s attitude.

Arora(15) studied on India’s greatest vital economic pillars and primary sources of foreign cash are the garment industry. More than forty million people in India are employed by the textile industry, making it the most significant employer in the nation. The people of India come from all around the country, each with their own set of traditions and customs. This results in a wide variety of traditional styles of clothing that date back centuries. India’s textile and garment industries have a rich history of producing high-quality goods that have gained acclaim all around the world. Cotton, silk, and denim produced in India are highly sought for around the world, and with the development of Indian creative talent, Indian garments have also become a hit in the world’s most prestigious fashion capitals. The textile and clothing industry in India is massive because of the country’s wealth of raw materials and production capacity. The current textile sector is estimated at US$ 33,23 billion, with unstitched clothing making up US$ 8,307 billion of the total. The industry’s impact on the economy is substantial, both in terms of its domestic market share and the amount of goods it exports. It contributed 14,0 % of factory production and 4,78 % of exports in 2013–14.

Vishwakarma(16) studied on the idea of circular fashion has deep roots in India’s cultural heritage; it is only now emerging on the modern fashion scene. Indicate a relationship of manufacturing and utilization procedures is crucial for saving our environment and its ecosystem and reducing the negative effect of fashion brands and consumption on environment degradation. It is clear that the solutions to the social, environmental, and economic problems that the fashion industry and its consumers are currently facing lie in the mass acceptance of circular fashion techniques. Sustainable fashion necessitates the integration of sustainable fashion technologies with handloom products skills at every level of the fabric production and consumption cycle.

Adamkiewicz(17) studied of the tremendous impact that such a business sector has on the environment, the fashion industry is at the center of the environmental storm. In order to realize the full potential of a recycling and reuse, the fashion industry must rapidly adopt far more mindful business methods that will influence customers to alter their attitudes and preferences in favor of circular items and services. When companies stop engaging in going green and instead work to win back consumers’ trust, they boost public opinion of the fashion industry as a whole.

Roozen(22) studied on environmental impact, the fashion industry ranks high. Constant resource extraction to support rapidly shifting fashion trends is a major environmental stressor. Recent research suggests that “prodding” could be a useful method for persuading people to take environmentally friendly actions. The purpose of this research was to find out if consumers may be nudged towards making more sustainable clothing decisions. N = 288 participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups: verbal push, visual persuade, or neutral. The results demonstrated that the verbal push, and to a lesser degree, the visually nod, significantly increased the likelihood that consumers would select the environmentally friendly option. The nudges also increased consumers’ propensity to spend for eco-friendly garments. This data demonstrates that pushing is an effective strategy for encouraging shoppers to select more eco-friendly garments.

Hasbullah(14) studied on increase in fashion at the detriment of nature. Both excessive consumption and pollution should function as a remember waking call to the international effort to promote more sustainable and socially conscious practices. In particular, it necessitates a radical change in the way people shop, with the emphasis shifting from traditional to environmentally friendly goods. The need for and dedication to environmentally responsible clothing consumption cannot be fostered without first knowing the elements that influence choices made by consumers. As part of the United Nations’ ongoing campaign to encourage more responsible consumption around the world, researchers in Malaysia set out to identify the variables that encourage people to buy eco-friendly clothing. The role of trend awareness as a moderator of the result was also investigated.

Mohr(18) studied on critical synthesis of the research done on sustainable fashion, the socially responsible industry, and the ideas that can explain why this is happening. The next step is to build on this research by creating a new concept on how to promote sustainable fashion, particularly among younger generations who have been instrumental in propelling and embracing this trend. This research presents the triple-trickle hypothesis, which integrates the establishment’s and industry’s roles in the dissemination of sustainable fashion and the identification of potential trickle-effects in the field of fashion studies.

Mahadewi(19) studied on knowledge of how educating millennials about environmental protection science influences their preference for ecologically benign goods. This insight will be attained by examining the proof provided by the modern, scientific study of biology. To acquire the most up-to-date information about millennials’ level of consciousness, we focus on articles published between 2010 and 2020. We begin our research by establishing a foundational familiarity with the text and its relevance to the study’s overarching theme. We then code the data, evaluate it, and interpret it in depth to arrive at a result that addresses legitimate research questions. Millennials’ consumption patterns of eco-friendly products are discussed, and it is concluded that there is strong link among environmental literacy and their preferences.

Johnstone(12) studied into whether and how millennials’ commitment to environmental responsibility extends to their clothing purchases. Comparing existing theories of reasoned action, the study tested an experiment on 448 European millennials and found that confidence in facilitators like famous promoters, instead of the new strategy of fashion merchants, often influenced buying intentions. It hints that fashion companies should employ influencers strategically to promote eco-friendly clothing.

Mishra(20) studied on adoption sustainable solutions in light of growing social, financial, and environmental concerns. The consumer market has shifted toward more environmentally friendly goods as more attention has been paid to sustainable production. Consumers’ actions in relation to the purchase of sustainable products are defined by the level of engagement they display. More study is needed to fill up the gaps in our knowledge of sustainable consumption in developing economies. Data was gathered using a questionnaire method from the millennials of India that is knowledgeable about the benefits of using environmentally friendly items and the negative effects of their lack of use.

Roxas(21) studied on the size of the global millennial or generation Y market, this study draws on social psychological and organizational theories to investigate the influence of societal and regulatory forces on millennials’ eco-brand preferences. In this study, we examine green customer behavior from the viewpoints of young people in a developing country, a scenario that has received less attention in the published literature. With responses from 354, the authors of this study examined the impact of interpersonal and governmental structural factors on the fundamental concepts of social cognition theory. To establish the relevant empirical connections and links of the suggested model’s components, the researchers used a partial least squares technique to route research. Internal drivers of millennials’ orientation toward green or ecologically friendly products are shown to be significantly influenced by the social-institutional context.

METHODOLOGY

The study intended to test the moderating role of consumer’s satisfaction with consumer’s attitude as shown in figure 2. This study also investigates the relationship between purchase action with quality consciousness, price consciousness, benefits, with an emphasis on the moderating mechanism played by millennial customer satisfaction with sustainable fashion. Companies must take additional steps to educate millennial consumers about the importance of environmentally friendly clothing. For millennial buyers, the price and the perceived benefits of sustainable clothing are key variables that influence their purchasing decisions. For the purpose of gathering cross-sectional data from 477 millennials who shop for fashion, a positivistic methodology and an online survey administered via the internet were used. In order to assess the proposed hypotheses, descriptive and MANOVA test is used.

Figure 2. Conceptual model for moderator analysis

RESULS AND DISCUSSION

According to table 1 price consciousness (PC) has mean score of 4,24 and SD is 1,13. Mean score of PC is highest among all. Quality consciousness (QC) has mean score of 4,20 and SD is 1,04. Consumer’s satisfaction (CS) has mean score of 4,09 and SD is 1,25. Consumer post purchase behaviour (CP) has mean score of 4,07 and SD is 1,23. Perceived benefits (PB) has lowest mean score which is 3,66.

|

Table 1. Descriptive table of millennial consumers (N=477) |

|||||||

|

Variables |

N |

Missing |

Mean |

Median |

SD |

Minimum |

Maximum |

|

PC |

477 |

0 |

4,24 |

5 |

1,13 |

1 |

5 |

|

PB |

477 |

0 |

3,66 |

4 |

1,59 |

1 |

5 |

|

QC |

477 |

0 |

4,20 |

5 |

1,04 |

1 |

5 |

|

CS |

477 |

0 |

4,09 |

4 |

1,25 |

1 |

5 |

|

CP |

477 |

0 |

4,07 |

4 |

1,23 |

1 |

5 |

According to table 2 an interaction in a two-way analysis of variance (MANOVA) provides a useful analogy for understanding the interaction effect. Whether or not the effect of price consciousness is constant across perceived benefits is a question of whether or not there is an interaction effect. The interaction effect is another way of determining if the perceived benefits have the same effect on price consciousness, and it serves the same purpose. The p-value (value in the “Sig.” column) will be less than ,05 (i.e., p,05) if the interaction effect is significant statistically. In contrast, the interaction effect isn’t really statistically significant if p >,05. If you look at the Wilks’ Lambda row, you’ll see that the p value is less than ,0004, indicating the presence of a significant interaction effect. This indicates that the perceived benefits have a different influence on the dependent variable variables. There was a statistically significant interaction effect between price consciousness, quality consciousness and perceived benefits on the combined dependent variables, F (4, 866) = 3,85, p =,004; Wilks’ Λ = 0,965.

|

Table 2. Multivariate tests of millennial consumers |

||||||

|

|

Effect |

Value |

F |

df1 |

df2 |

p |

|

Price consciousness (PC) |

Pillai’s Trace |

0,6456 |

51,71 |

8 |

868 |

< ,001 |

|

|

Wilks’ Lambda |

0,355 |

73,32 |

8 |

866 |

< ,001 |

|

|

Hotelling’s Trace |

1,8108 |

97,78 |

8 |

864 |

< ,001 |

|

|

Roy’s Largest Root |

1,8092 |

196,30 |

4 |

434 |

< ,001 |

|

Perceived benefits (PB) |

Pillai’s Trace |

0,3023 |

19,32 |

8 |

868 |

< ,001 |

|

|

Wilks’ Lambda |

0,698 |

21,35 |

8 |

866 |

< ,001 |

|

|

Hotelling’s Trace |

0,4333 |

23,40 |

8 |

864 |

< ,001 |

|

|

Roy’s Largest Root |

0,4333 |

47,01 |

4 |

434 |

< ,001 |

|

Quality consciousness (QC) |

Pillai’s Trace |

0,1061 |

6,08 |

8 |

868 |

< ,001 |

|

|

Wilks’ Lambda |

0,896 |

6,14 |

8 |

866 |

< ,001 |

|

|

Hotelling’s Trace |

0,1147 |

6,19 |

8 |

864 |

< ,001 |

|

|

Roy’s Largest Root |

0,0951 |

10,32 |

4 |

434 |

< ,001 |

|

PC * PB |

Pillai’s Trace |

0,1917 |

4,18 |

22 |

868 |

< ,001 |

|

|

Wilks’ Lambda |

0,812 |

4,33 |

22 |

866 |

< ,001 |

|

|

Hotelling’s Trace |

0,2281 |

4,48 |

22 |

864 |

< ,001 |

|

|

Roy’s Largest Root |

0,2088 |

8,24 |

11 |

434 |

< ,001 |

|

PC * QC |

Pillai’s Trace |

0,1328 |

3,43 |

18 |

868 |

< ,001 |

|

|

Wilks’ Lambda |

0,869 |

3,49 |

18 |

866 |

< ,001 |

|

|

Hotelling’s Trace |

0,1475 |

3,54 |

18 |

864 |

< ,001 |

|

|

Roy’s Largest Root |

0,1265 |

6,10 |

9 |

434 |

< ,001 |

|

PB * QC |

Pillai’s Trace |

0,0942 |

2,68 |

16 |

868 |

< ,001 |

|

|

Wilks’ Lambda |

0,908 |

2,69 |

16 |

866 |

< ,001 |

|

|

Hotelling’s Trace |

0,0997 |

2,69 |

16 |

864 |

< ,001 |

|

|

Roy’s Largest Root |

0,0709 |

3,84 |

8 |

434 |

< ,001 |

|

PC * PB * QC |

Pillai’s Trace |

0,0346 |

3,82 |

4 |

868 |

0,004 |

|

|

Wilks’ Lambda |

0,965 |

3,85 |

4 |

866 |

0,004 |

|

|

Hotelling’s Trace |

0,0358 |

3,87 |

4 |

864 |

0,004 |

|

|

Roy’s Largest Root |

0,0358 |

7,77 |

2 |

434 |

< ,001 |

The analysis’s next step is to evaluate H4, which hypothesises that The moderated-mediation(43,44) model is tested for this study using the Hayes Process Macros with SPSS at 10,000 bootstrapping, i.e., the moderating effect of Millennial customer satisfaction works as a moderator between participation and MCA. Model 7 of(35) Process Macros with SPSS is used to test this hypothesis, and figure 3 displays the outcomes of this model of mediator moderation. To assert that mediation is moderated, one should (if not also must) have proof that at least one of the paths in the X! M! Y system is moderated.(36)

Figure 3. Results of moderated-mediation model

According to(36), the model is known as moderated-mediation when a mediator modifies its impact on the result variable under the influence of increasing amounts of another variable (moderator). These models are tested in the psychology field, but are new in marketing studies, for example, see(37,38,39,40), They examine the change in indirect effect owing to the inclusion of a moderator variable (2019). According to this method, if the upper limit confidence interval (ULCI) does not include zero and the lower limit confidence interval (LLCI) does not include zero, the hypothesis is accepted.(36) With a moderated-mediation index value of 0,7745, a standard error of 0,0327, and confidence intervals (CI) limitations, the finding supports the mediating role of MCS (0,7102, 0,8388) as shown in figure 2. Significant at p 0,05 and CI bounds, the indirect effect of customer attitude and MCA is 0,0497. (-0,2180, 0,2933). Studying the role of customer satisfaction with purchase behaviour and its impact on consumer attitude was interesting.(41,42) The evidence for customer satisfaction as a beneficial moderator supporting the favourable association between purchase behaviour and attitude was presented by the moderation analysis. According to the study, there is a stronger association between high consumer involvement and MCS than low customer involvement (figure 4).

Figure 4. Graph representing the moderating effect of consumer satisfaction

CONCLUSION

This study conclude that millennials are now turning into a growing generation that is aware of the long-term repercussions of the low pricing of quick fashion. People are gaining a greater understanding of the history of the clothing they wear as well as the manufacturing methods that go into creating it. After coming to this realization, the majority of millennials will want to take action to safeguard the Earth, which they now consider to be their home. They are a welcoming and helpful group of people. They cannot sit idly and do nothing as dreadful things happen to our environment; thus, promoting fashion brands that are committed to ethical practices is only one small part of the selfless actions they are making to protect the world. This youth of today is specifically focusing on the fashion business to alter its practices that aren’t environmentally friendly. Those who are part of Generation Z or the millennial generation are the ones most inclined to purchase things depending on their principles. Because of their increased purchasing power, members of the growing generation Z market are putting pressure on fashion businesses to sustain their business strategies in order to remain competitive and secure their place in the market.

REFERENCES

1. Wiedmann KP, Hennigs N, Siebels A. Value‐based segmentation of luxury consumption behavior. Psychology & Marketing. 2009 Jul; 26(7): 625-651.

2. Henninger CE, Alevizou PJ, Oates CJ. What is sustainable fashion?. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal. 2016 Oct 3; 20(4): 400-216.

3. Arora N, Manchanda P. Green perceived value and intention to purchase sustainable apparel among Gen Z: The moderated mediation of attitudes. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing. 2022 Apr 3; 13(2): 168-185.

4. Wiebke A. The Fast Fashion Epidemic. The University of Arizona. 2020.

5. Ricci C, Marinelli N, Puliti L. The consumer as citizen: the role of ethics for a sustainable consumption. Agriculture and agricultural science procedia. 2016 Jan 1; 8: 395-401.

6. Hill J, Lee HH. Young Generation Y consumers’ perceptions of sustainability in the apparel industry. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal. 2012 Sep 14; 16(4): 477-491.

7. Naderi I, Van Steenburg E. Me first, then the environment: Young Millennials as green consumers. Young Consumers. 2018 Aug 7; 19(3): 280-295.

8. Schawbel D. New findings about the millennial consumer. Forbes: Entrepreneurs. 2015.

9. Khare A, Sadachar A. Green apparel buying behaviour: A study on I ndian youth. International Journal of Consumer Studies. 2017 Sep; 41(5): 558-569.

10. Kumar D, Gupta P. Ethical Branding Best Practices: A Study of Fabindia in the Context of Social Business. In Ethical Branding and Marketing 2019 Apr; 15: 115-124.

11. Advani S. How commoditization and cross-cultural values influence the sustainability of small-scale fisheries in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India (Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia). 2020.

12. Johnstone L, Lindh C. Sustainably sustaining (online) fashion consumption: Using influencers to promote sustainable (un) planned behaviour in Europe’s millennials. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 2022 Jan 1; 64: 102775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102775

13. Kim Y, Oh KW. Which consumer associations can build a sustainable fashion brand image? Evidence from fast fashion brands. Sustainability. 2020 Feb 25; 12(5): 1703. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051703.

14. Hasbullah NN, Sulaiman Z, Mas’ od A, Ahmad Sugiran HS. Drivers of sustainable apparel purchase intention: An empirical study of Malaysian millennial consumers. Sustainability. 2022 Feb 9; 14(4): 1945. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14041945.

15. Arora S. Factors Affecting Indian Apparel Industry (Doctoral dissertation). 2022.

16. Vishwakarma A, Meena ML, Dangayach GS, Gupta S. Identification of challenges & practices of sustainability in Indian apparel and textile industries. InRecent Advances in Industrial Production: Select Proceedings of ICEM 2020. Springer Singapore. 2022: 149-156.

17. Adamkiewicz J, Kochanska E, Adamkiewicz I, Łukasik RM. Greenwashing and sustainable fashion industry. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry. 2022: 100710.

18. Mohr I, Fuxman L, Mahmoud AB. A triple-trickle theory for sustainable fashion adoption: the rise of a luxury trend. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal. 2022 Jul 13; 26(4): 640-660.

19. Mahadewi EP, Harahap A, Alamsyah M. The Impact of Environmental Protection Education on Millennial Awareness Behavior on Sustainable Environmentally Friendly Products: A Systematic Review of Modern Biological Sciences. Annals of the Romanian Society for Cell Biology. 2021 Apr 2: 8475-8484.

20. Mishra S, Shukla Y, Malhotra G, Chatterjee R, Rana J. Millennials’ self-identity and intention to purchase sustainable products. Australasian Marketing Journal. 2023 Aug; 31(3): 199-210.

21. Roxas HB, Marte R. Effects of institutions on the eco-brand orientation of millennial consumers: a social cognitive perspective. Journal of consumer marketing. 2022 Feb 9; 39(1): 93-105.

22. Roozen I, Raedts M, Meijburg L. Do verbal and visual nudges influence consumers’ choice for sustainable fashion?. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing. 2021 Oct 2; 12(4): 327-342.

23. Böcker L, Meelen T. Sharing for people, planet or profit? Analysing motivations for intended sharing economy participation. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions. 2017 Jun 1; 23: 28-39.

24. Hamari J, Sjöklint M, Ukkonen A. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. Journal of the association for information science and technology. 2016 Sep; 67(9): 2047-2059.

25. Konuk FA. The effects of price consciousness and sale proneness on purchase intention towards expiration date-based priced perishable foods. British food journal. 2015 Feb 2; 117(2): 793-804.

26. Tariq M, Abbas T, Abrar M, Iqbal A. EWOM and brand awareness impact on consumer purchase intention: mediating role of brand image. Pakistan Administrative Review. 2017; 1(1): 84-102.

27. Chan HY, Boksem M, Smidts A. Neural profiling of brands: Mapping brand image in consumers’ brains with visual templates. Journal of Marketing Research. 2018 Aug; 55(4): 600-615.

28. Foroudi P, Jin Z, Gupta S, Foroudi MM, Kitchen PJ. Perceptional components of brand equity: Configuring the Symmetrical and Asymmetrical Paths to brand loyalty and brand purchase intention. Journal of Business Research. 2018 Aug 1; 89: 462-474.

29. Aakko M, Niinimäki K. Quality matters: reviewing the connections between perceived quality and clothing use time. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal. 2022 Mar 1; 26(1): 107-125.

30. Stöcker B, Baier D, Brand BM. New insights in online fashion retail returns from a customers’ perspective and their dynamics. Journal of Business Economics. 2021 Oct; 91(8): 1149-1187.

31. Brandão A, Da Costa AG. Extending the theory of planned behaviour to understand the effects of barriers towards sustainable fashion consumption. European Business Review. 2021 Feb 24; 33(5): 742-774.

32. Chang HJ, Watchravesringkan KT. Who are sustainably minded apparel shoppers? An investigation to the influencing factors of sustainable apparel consumption. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management. 2018 Jan 29; 46(2): 148-162.

33. Gupta S, Gwozdz W, Gentry J. The role of style versus fashion orientation on sustainable apparel consumption. Journal of Macro marketing. 2019 Jun; 39(2): 188-207.

34. McNeill L, Moore R. Sustainable fashion consumption and the fast fashion conundrum: fashionable consumers and attitudes to sustainability in clothing choice. International journal of consumer studies. 2015 May; 39(3): 212-222.

35. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression - Based Approach, 1st ed., Guilford Press, New York, NY. 2013.

36. Hayes AF. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate behavioral research. 2015 Jan 2; 50(1): 1-22.

37. Nyadzayo MW, Khajehzadeh S. The antecedents of customer loyalty: A moderated mediation model of customer relationship management quality and brand image. Journal of retailing and consumer services. 2016 May 1; 30: 262-270.

38. Guo G, Tu H, Cheng B. Interactive effect of consumer affinity and consumer ethnocentrism on product trust and willingness-to-buy: a moderated-mediation model. Journal of Consumer Marketing. 2018 Dec 4; 35(7): 688-697.

39. Djelassi S, Diallo MF, Zielke S. How self-service technology experience evaluation affects waiting time and customer satisfaction? A moderated mediation model. Decision Support Systems. 2018 Jul 1; 111: 38-47.

40. Nagaraj S, Singh S. Investigating the role of customer brand engagement and relationship quality on brand loyalty: an empirical analysis. International Journal of E-Business Research (IJEBR). 2018 Jul 1; 14(3): 34-53.

41. MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate behavioral research. 2004 Jan 1; 39(1): 99-128.

42. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior research methods, instruments, & computers. 2004 Nov; 36(4): 717-731.

43. Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate behavioral research. 2007 Jun 29; 42(1): 185-227.

44. James LR, Brett JM. Mediators, moderators, and tests for mediation. Journal of applied psychology. 1984 May; 69(2): 307-321.

FINANCING

No financing for the article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest in the work.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Beeraka Chalapathi; G. Rajini.

Research: Beeraka Chalapathi; G. Rajini.

Writing - original draft: Beeraka Chalapathi; G. Rajini.

Writing - revision and editing: Beeraka Chalapathi; G. Rajini.